Erstellt am: 24. 10. 2015 - 11:55 Uhr

Peronism

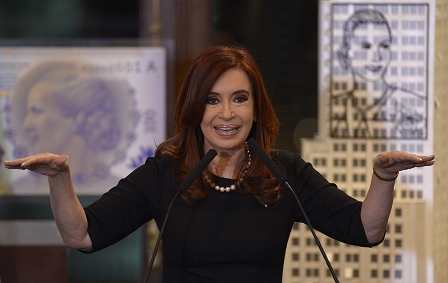

Argentinians are heading to the polls this weekend. And big changes are set to be on the way. After almost 9 years in the top job, one of the most charismatic politicians of South America, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is leaving office.

We discussed where Argentina is at in 2015 in a Reality Check Special, broadcast on Saturday October 24th at 12 midday. Contributions came from Dr. Ana Margheritis at the University of Southampton, Roberto Herrscher Rovira at the University of Barcelona, Celia Szusterman, Director, The Institute for Statecraft's Latin America Programme, Nicolas Simone a political analyst in Buenos Aires, Drew Reed Guardian Newspaper correspondent in Buenos Aires.

Public Domain

Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is stepping down as President of Argentina. Her party is the Justicialist Party or PJ. It is a Peronist political party and the largest faction of the Peronist movement. But who are the Peronists essentially, what is their affiliation to the myth and historical figures of Juan and Eva Perón and therefore what relevance does all of this have for young Argentinains voting on Sunday?

For some context on the Peronist movement, I spoke with Dr. Ana Margheritis at the University of Southampton, author of Argentina's Foreign Policy: Domestic Politics and Democracy Promotion in the Americas.

Steve: Who or what is Peronism?

Ana: Well there's no simple explanation. It emerged back in the 1940s as a labor-based political party. (Juan) Perón helped to institutionalise workers' rights with the state at the centre stage of the development process. It encouraged (things like) nationalist economic policies, industrialization via substitution of imports, the expansion of the domestic market and access to social benefits. And therefore it encouraged, indirectly, social mobility that certain sectors of the Argentinian population didn't have before.

Steve: But Perón was forced out of the country before returning briefly (once more) to power.

Ana: He was exiled for almost 2 decades and when he came back, Argentina was in a continuous process of decline and violence, particularly in the late 60s and 1970s. And since his death, Peronism has become a fragmented political movement that now revolves around the competition between various factions. (These factions or parties) reflect the flexibility on the ideology (of Peronism) as to accommodate positions on both the right and the left.

Steve: So is it a case of hanging on to the name (of Perón) and fitting a party into the public mood?

Ana: I'm not sure if it is a fit into the public mood (but modified) It is probably into new versions of Peronism named after the leaders. And in the 90s it was called Menemism (after the then leader Carlos Menem) and adapted to a neoliberal line. Now it is identified with Kirchnerism because of the Kirchner family (the late President Nestor Kirchner and his wife, current President Cristina Kirchner). Those labels show the importance within the movement of leadership.

APA/AFP/JUAN MABROMATA

Steve: Juan Perón and his wife Eva Perón are figures in history, so do they have any relevance to the main challenges that young Argentinians face in 2015?

Ana: Well, they keep being used as charismatic references in political discourse. Both figures are influential because Argentina still follows a certain tradition of patrimonialism and strong leadership. For citizens who look up to their leaders in such a way, this may be influential. And also the myth of these two main figures was built around the idea of those who were dispossessed, the "have-nots" in society, appealing to their expectations and dreams. At that time, the couple attracted the aspirations of workers and other groups like women. Those who sought inclusion and better standards of living, they found in those leaders a promise of protection and provision of benefits. If you look at Argentina today, it is a country where important segments of the population experience daily exclusion even if the socio-economic conditions have changed. So the references to the myths may still work.

Steve: Cristina Kirchner when she leaves office is said to leave behind a divided country. In what way is Argentina divided?

Ana: It’s true. There are several lines of division and some of them have been exacerbated by the Kirchners. If you look at some of the statistics on unemployment, poverty, those were reduced and that’s good news. But the government attained that result through social assistance mostly in the way of subsidies that reproduces the conditions of poverty and clientalism. There are some forms of poverty and marginalisation that have become structural and the conditions for overcoming those situations have not been created. And that creates a division. Also if you look at Kirchner’s high investment in changing the narrative of national history that is another source of divisions; they have been playing politics with a confrontational logic with a zero sum game. They underestimated the constructive role of dissent and dialogue that characterises society in democracies. And they resorted to nationalist ideas, they condemned those who disagreed, they accused those who disagreed of plotting against the government or not caring for the interests of the country. They polarize politics and they reduce politics to either be with me or against me. The campaign reflects that manipulation of fear and they use the idea that if you don’t vote for me another crisis will happen.