Erstellt am: 29. 5. 2015 - 17:10 Uhr

The Politics of Pollution

Robert Bullard, known as the father of environmental justice, looks dapper and spritely despite a long flight in from Texas. As we leaned over the balustrade on a roof top bar, he admired the Viennese trams passing below and told me why, for him, environmentalism is an extension of the American civil rights movement:

“By law for more than a hundred years it was legal to dump on poor people, to dump on people of people of colour. The most important indicator of health in the USA is one's zipcode. Tell me where someone lives and I'll tell you how healthy they are likely to be.”

Robert Bullard

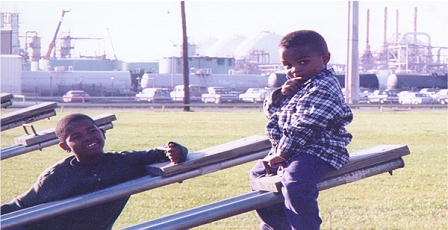

What does that mean? Bullard’s three decades of research have shown that toxic and industrial facilities were overwhelmingly concentrated in African-American and low-income neighbourhoods. Coal-fuelled power plants belch soot over communities, over children’s playgrounds – noxious smelling clouds of sulphur dioxide, arsenic and mercury.

"Money Talks"

Bullard, a sociologist, calls this phenomenon “the path of least resistance”. Traditionally these communities haven’t had the money or political influence to kick up a fuss when a new landfill or coal-fired power station or petrochemical plant is put near their homes.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

People make a lot of money out of our demand for the oil refineries and the chemical plants, but the waste these vehicles of profit produce are kept well out of sight of their manicured lawns. The share-holders and executives of these lucrative but dirty industries live a long way away, of course, breathing clean air and fighting tooth and nail against any regulation that might curb noxious emissions. It’s not fair, but money talks.

"They get sick and sometimes they die"

“The people that produce the most pollution really don’t have to suffer the consequences. And to add to the injustice people living with industrial pollution next door, they don’t get the jobs. They get pollution, they get sick and sometimes they die”

Robert Bullard

Bullard was in Vienna to address the 8th edition of the annual Earth Talks about a US national issue that mirrors the global inequity of climate change and pollution. He calls it the politics of pollution. Money buys you a free pass from facing up to the consequences of heavy industry. They fight legislation – complaining of the “overreach of big government” because it is not their kids getting asthma, it’s not their families getting cancer. It is someone else: someone poor.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

Bullard’s research has shown that the asthma rate is 35% higher for African Americans than it is for whites and that African Americans are 79% more likely to live where industrial pollution poses the greatest health danger.

Bullard, a sociologist, found his life’s quest while carrying out some research for a legal case on which his wife, a lawyer, was working in Houston. It was the first US case dealing with the concept of “environmental discrimination”. Bullard found that even though blacks only made up 25 percent of the population, 100 percent of city-owned landfills were located in predominantly black neighbourhoods.”

Poor Lives Matter

He dug deep and found that across the country it was a similar story. He has written 18 books but laughs that “it’s actually just the same book; it’s about equity, it’s about social responsibility and it’s about the need for change.” In recognition of his work in tirelessly highlighting and fighting the injustice of environmental policy, the magazine Newsweek has named him one of thirteen environmental leaders of the 21st century.

Of course Bullard is not campaigning to have these refineries dumped in the middle of Beverly Hills. He is campaigning the have the rich and politically-influential classes to face up to the environmental damage they are inflicting on their fellow citizens. Poor lives matter. “The environmental justice movement is not about spreading pain, it’s about eliminating or reducing those problems for everybody.”

Robert Bullard

He says a more just and more sustainable America means moving towards renewable and clean energy and away from a system that encourages one person per car. Again he looks out at a tram: “You have this public transport system, in American cities we used to have this and the car giants lobbied against it.”

US asthma rates have trebled in the three decades between 1980 and 2009 and now cost $56billion dollars in medical costs every year. Imagine if you sank $56 billion dollars every year in making cities more liveable, or investing in clean energy. Environmentalist like Bullard the society is condemned to endlessly pay to treat symptoms of a perverse industrial policy instead of tackling the root causes.

But if you do get sick, and you believe it is because you live near an industrial plant, it is very difficult to make your case in court. Lawyers can stretch out the cases for years, and, to put it bluntly, neither time nor money is on the side of those suffering the illnesses. But Bullard told me that by organising and uniting the victims are fighting back:

Barbara Köppel

“In the past two weeks we’ve been able to get the federal government to strengthen the Clean Energy Act when it comes to power plants and refineries. And this success came despite massive push back from the oil companies. You need a little bit of patience and a lot of work.”

In fact, he says, fighting the power of money can feel exhausting. He likens it to “swimming upstream”, before opting for a different sporting metaphor: “It’s not just a marathon, it’s a marathon relay. You run the race and hand of the baton. It never stops.”

Bullard is now 68, and even though he is still fizzing with enthusiasm for his quest for environmental justice, he says it is time to hand over that baton to the younger generation. “What gives me hope is that my students have made this cause their own. And now I see students of my students fighting the same fight. We have lots of troops out there doing this work.”

It’s a basic right to have clean air to breathe, he says, and that right should always trump the lobbying of big business.