Erstellt am: 10. 1. 2015 - 19:45 Uhr

"Unite before it is too late!"

Pete Jordan, a Californian author, long-time drifter and bike-enthusiast moved to Amsterdam at the beginning of this century because he wanted, as he admitted to bemused locals, to live in city where he could "be stuck in a bicycle traffic jam at midnight."

It's become such a tiresome orthodoxy that car-dominated, smog-polluted cities are inevitable that we're led to believe that cities would collapse into chaos if a single line of parking spaces were removed. Amsterdam, as Jordan describes in his book "In the City of Bikes", has proved that an alternative is possible.

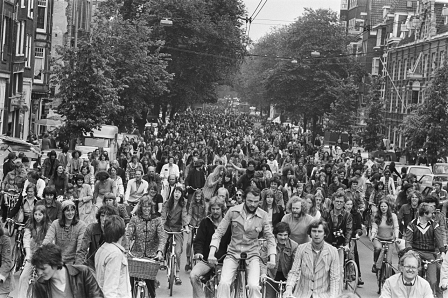

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

At the turn of the century, cycling was exploding in popularity across the West, after Henry Ford developed the first mass-produced automobile, most wealthy cities fell in love with caged motorised status-symbols. Yet the pragmatic Dutch, who even had two cycling Queens, mostly stuck to cycling for inner-city travel. And despite a distinct political campaign to heavily motorise the population in the 1960s, with a resulting sharp dip in cycling enthusiasm, Amsterdam has steadily remained one of the most enthusiastic cycling cities in the world ever since.

An estimated 881.000 (57%) of Amsterdammers use their bike on a daily basis. There are estimated to be 157 bike shops. As Pete Jordan describes, you can flirt on your bike or even use one as a maternity ambulance. Cycling in Amsterdam is a way of life.

New Battles/Old Battles

If there is a lesson in Jordan's book, it's that Amsterdam's status as a bike-friendly "cycling paradise" was hard won and that politics and people's power matters. The modern political battles for space are very old battles in Amsterdam: "The city government did almost nothing for cyclists for years", Jordan told me via Skype from Amsterdam. "They didn't put in special bike racks or bike lanes or any infrastructure."

A Delusion

Jordan unearths a letter to the editor of De Telegraf in Amsterdam from 1926, in which an enraged cyclist quoted a municipal plan to ban cyclists from a main Amsterdam thoroughfare lined with luxury shops on the grounds that, in the words of one critic, "bicycle riders are generally not buyers." It sounds eerily like the recent battles over the Mariahilfestraße in Vienna.

CityOfBikes.Com

In the 1920's, the prescient Amsterdam letter writer urges the cyclists to "unite", to be aware of the power of their numbers, because politics was skewed in favour of the car-driver: "Despite all our democratic airs, a delusion is now developing in the heads of our authorities and of ourselves. And just as a swamp produces mosquitoes, this delusion will cause a nuisance: the idea that ten cyclists are less important than a single motorist."

In the 1960s, roads were closed to cyclists but kept open for motorists because the car-lobby was better politically organised. Jordan, paraphrasing the response of a Dutch civil engineer, explains: "Motorists, though constituting a small minority of road users at the time, almost universally belonged to politically active motorist organisations. More important, virtually anyone who had influence over traffic policy (elected officials, high-ranking civil servants, etc.) either owned a car or, as a job perk, had one at his or her disposal."

By the 1960s, Amsterdam's politicians were openly advocating filling picturesque canals to provide more space for parking cars and, with increasingly busy streets, H Tielrooy, the chief inspector of Amsterdam's traffic police claimed that cycling in the city was "tantamount to committing suicide." As the number of cyclists dropped, the number of car drivers rose and "the number of traffic deaths in Amsterdam reached ever higher levels."

Indeed what is surprising about Jordan's research of the cultural history of cycling in Amsterdam is how from the very beginning cyclists have been derided and insulted as "dancing gnats", "street fleas", "hornets", "lurking hyena", "bacteria of the street", "overgrown vermin" and even, by former police chief Jelle Kuiper as "elephants". Jordan prefers to view them as "indestructible cockroaches. In spite of all they have endured over the past century, the city remains overridden with them."

Ferris Jordan

The White Bicycles

The Amsterdam cyclists, who had been forced into meekness in other cities, fought back fiercely and demanded their rights. The first group to have an impact was a mischevious group calling itself Provo surfaced in 1965 and announced it was committed to fight the "asphalt terror of the motorized bourgeoisie". It introduced a free service providing for public-use bicycles, the so-called "White Bicycle" with the bikes themselves provided by the repairing – the masses of old wrecks that were hitherto being used for scrap metal.

Provo created a pilot project, hoping the government would invest and provide thousands of white bikes, but instead police reacted by impounding their first three bikes – the idea of providing free unlocked bikes was seen as tantamount to encouraging theft. A few days later a Provo activist, who was spraying some scrap bikes white, was struck by the police with a baton. The project was ultimately crushed in 1967 when the city council rejected the Provo scheme, but as Jordan writes, a seed had been sewn, "White Bikes would live on as a key symbol of Amsterdam as a countercultural center" and would eventually lead to cycle-sharing schemes like the one in Vienna.

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

The pro-cycling protests continued. In the early 1970s an activist group called "De Lastige Amsterdammer" ("The Troublesome Amsterdammer"), made up largely of medical students concerned by the health-impact of an increasingly car-dominated society, started riding around town slowly on cargo bikes – known as bakfietsen – arguing that "On a bakfiets, we're taking up as much room as a small car, but we aren't spewing exhaust: we aren't honking; we aren't mowing down children; and we aren't rumbling like thunder. So now who's the crazy one?" An interviewer asked the activist Henk Bakker why his group has stopped the traffic? "We, ourselves, were traffic."

At the same time a group called the Kabouters (meaning "The Gnomes") announced a Car-Elimination Service and stopped cars using an entrance to the Leidsestraat - the shopping street that had become a focal point of mobility issues. As a political party the Kabouters won 38.000 votes and three seats on the city council in the 1970 municipal elections. Pro-cycling activism was becoming mainstream and received a boost from the 1973 oil crisis. Nationwide cycling demos followed, the rise of cars was stemmed and cycling re-established as an integral part of Amsterdam's city culture.

A Love Affair

Jordan has become so enamoured with cycling culture in Amsterdam that he has vowed stay "forever" in the city dreaming of riding deep into old age "wrist in hand" with his bike-mechanic wife Amy Joy, like the serene pensioners they spot infuriating motorised traffic in a city where cyclists seem to rule the roost. He delights in spotting the broad cross-section of society that is mobile on two wheels: from the hipster, to the straight-laced business community to glamorous women in evening dresses.

Yet the lesson of his book is if you want a cycling paradise, you have to fight for it. "Some many cities are now where Amsterdam was in the 1970s, when the city was taking its first steps to becoming a city that actively encourages cycling" Jordan told me, "This is three or four decades of active work. And every year Amsterdam is trying to improve its cycling infrastructure."