Erstellt am: 30. 4. 2014 - 14:37 Uhr

The Missing Thousands

When the Austrian polling booths open for this spring’s European Parliamentary elections, one significant part of the electorate will be largely absent.

According to the latest Eurostat figures, 352,000 residents of Austria from other EU member states. That's 4.5% of the total populations. They have the theoretical right to vote but less than 10% will be able to take advantage of that right when voting starts in Austria on the 25th of May.

chris cummins

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights explicitly stipulates that EU citizens residing in a member state different from their member state of nationality are entitled to vote (or even stand as candidates) in elections to the European Parliament "under the same conditions as nationals of that state". Yet, according to the Austrian Interior Ministry, only 33,948 non-Austrian EU-citizens have registered to do so.

In the idealistic view of the European Union as a borderless, mobile society, this figure seems shockingly low. If the hundreds of thousands of non-Austrian EU-citizens took advantage of their right to vote in this country it might significantly affect the outcome of the elections.

Bureaucratic Hurdles

So why don’t they vote?

It may be partly explained by apathy, but it is also matter of bureaucratic hurdles that many in Brussels would like to see removed. Whereas Austrian citizens appear automatically on the electoral register, non-Austrian EU-citizens (unless they have registered for previous Austrian elections) have to go through a registration process.

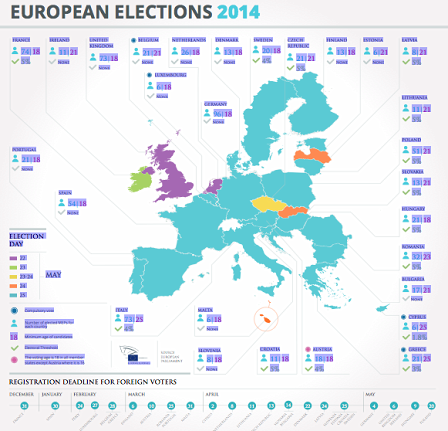

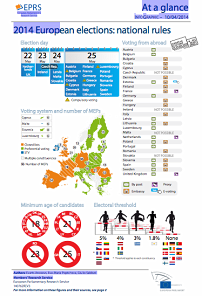

To an extent this makes sense. Since EU-citizens have the right to vote in either the elections in their country of birth or their country of residence, there is danger of "double voting". All EU member states have a registration deadline for foreign voters. These deadlines vary widely: In France foreign voters had to sign up by December 31st last year while in Poland registration ends on the 20th May - just a few days before the election.

European Parliament

Informed Too Late?

The problem in Austria seems to be one of information: the deadline for registration was the 11th March - a full month before the political parties launched their official campaigns. It seems only a minority of those bound by the deadline were aware of it.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

A "Scandalous" Lack of Information?

The Austrian Greens’ lead candidate at the European elections Ulrike Lunacek believes this is because of a lack of information from the Austrian authorities.

EPA /LUCAS DOLEGA

"The Austrian government and the Interior Ministry made a huge mistake not informing people on time," she told FM4 Reality Check, accusing the authorities of being "blind" to the needs of non-Austrian EU citizens in this country.

Lunacek says her party is attempting to verify claims that the Austrian Interior Minister Johanna Mikl-Leitner only informed the regional electoral offices about how process of the voting rights of non-Austrian EU residents just one day before the 11th March deadline. "This seems scandalous to me," says Lunacek.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

Certainly it seems other EU states managed a much better job of informing their "EU- foreigner" residents than Austria. Ulrike Lunacek, for example, who as an MEP has apartment in Brussels, says that as an Austrian citizen in Belgium she was notified in February by a letter from the Belgian authorities in Belgium explain how she could take part in the Belgian EU elections had she wished to do so.

In Austria there was no such direct contact.

Robert Stein, the Deputy Head of the Electoral Commission at the Interior Ministry, told me that the Interior Ministry had tried to raise awareness with an internet campaign and a newspaper advertisement but that the national constitution didn’t Austria to follow the Belgian example: "Austrian doesn’t have the direct possibility to write to every EU-citizen resident in the country," he said. "The Interior Minister can’t do it because she doesn’t have the necessary data bank at her disposal." He says changing the laws would require a two-thirds majority in parliament.

Disinterested or Disenfranchised?

To be fair to Austria past voting records suggest the low level of international engagement is not unusual in Europe. An estimated 8 million Europeans of voting age live outside the country they were born in. Although registrations by EU citizens to vote in their country of residence rather than origin have doubled in the past twenty years, from 5.9 percent in 1994 to 11.6 percent in 2009. Nine out of ten remain uninvolved.

The European Court of Justice has made clear that the administration of elections is up to individual member states but the issue is a problem for Brussels since such low participation is a challenge to the credibility of the European democratic process. As one Commission spokesman, quoted by the website EUobserver, put it "I don't think the issue is double voting here. The real problem is to get people out to vote."

The Lost Thousands

The low level of participation for mobile EU-citizens in the elections of their countries of residence wouldn’t be a problem if more of them were voting in their countries of birth. But it seems they are not.

It is very hard to pin down any statistics about cross-border voting. My many attempts to get figures from Brussels were answered with lots of sighs and promises "to call back later". No-one seemed to know exactly.

Having failed to vote in Austria, I could still vote in the British version - but again I would have to work hard to find out how. The British Embassy in Austria says that is has been using social media like Facebook and Twitter to draw attention to the possibility - which is all fine if you use social media and happen to follow your national embassy.

Robert Stein of the Austrian Electoral Commission says 34,011 Austrians who live outside Austria have registered to take part in the Austrian EU elections. Although it is difficult to pin down the exact number of those mobile-Austrians who would be eligible to vote, the best estimates suggest this figure means only around 10% are taking advantage of their right to vote here.

A Voting Hotchpotch

And although the decisions of the EU Parliament affect the lives of all EU citizens, there have been vast differences in accessibility to the European Parliamentary elections voting booths.

In the 2009 elections, for example, the EU Commission found that EU-citizens in Lithuania and Slovenia were only granted the right to vote after a minimum of five years’ residence. The rules seem to be a hotchpotch. As the group European Citizens Abroad points out on its website:

"An Irish citizen who lives in The Netherlands cannot vote for Irish Members of European Parliament, while a Danish citizen can vote for his country’s constituency even if he lives in another EU member state. However, a Danish citizen living in the US cannot vote at all, while a French citizen can. Some can only use postal voting, some can only vote at diplomatic posts, others enjoy both, and sometimes proxy voting or even e-voting."

European Parliament

It is the glorious variety of life within the European Union, but is it fair?

"The economic crisis has shown that Europe is at the centre of a lot of important decisions," the European Parliaments communications director Juana Lahousse Juarez told me recently, "and Parliament has more power than ever to be an actor."

Well with that extra power over European citizens, surely there also comes an obligation to ensure each European has his or her say on the MEPs who sit in that parliament? If the EU is to become more mobile, its voting system will have to keep up pace.

13 million EU citizens live in a "foreign" EU state. It is vital for EU democracy that they have a vote and a say in what happens at the EU Parliament. They need encouragement to vote, not hindrances.