Erstellt am: 20. 3. 2014 - 00:14 Uhr

"Criminal judicial approach to drugs doesn't work"

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

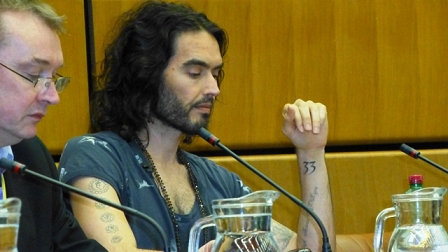

"The reason I am here is both as a recovering addict and an advocate for change in global drug policy and legality", said Russell Brand during a meeting of a Commission on Narcotic Drugs in Vienna. "As a person that lived as a drug addict for ages and ages I know that the criminal judicial approach to drugs does not work. It is completely ineffective."

chris cummins

Brand had visited the UN's Viennese headquarters to endorse the Support, Don't Punish campaign and sprinkle his celebrity stardust on an important annual policy meeting that rarely attracts much press coverage.

I had been anxious to meet Russell Brand in the flesh. He has become increasingly prominent as cultural commentator in recent months and I have always struggled to work out exactly the role he wants to play – is he the iconoclastic sage or just a provocative court jester?

Can he stay serious?

The comedian, who was once best known internationally for his marriage to pop star Katy Perry, has surprised many in recent months by writing some impressively weighty and insightful columns for the Guardian, particularly a memorable article on the legacy of Margaret Thatcher.

He also acted as the guest-editor of an edition of the venerable New Statesman newspaper, which was dedicated to "revolution". Rhetorically gifted, he is capable of formulating compelling arguments but then when those views are challenged, he tends to hide behind bawdy, childish comedy.

Having, for example, admirably lectured Jeremy Paxman, the BBC's top interviewer, on the futility of voting within the "pre-existing paradigm which is quite narrow and only serves a few people", he then giggled and squirmed in his seat when challenged on the alternatives, before finally resorted to complimenting Paxman's new beard.

Why couldn’t he stay serious?

Critics derided his performance. Brand, they said, was good for a sound bite but was incapable of thinking his arguments through. Typical superficial celebrity?

A spokesman for the disillusioned

But behind the pantomime lay an eloquently expressed disgust with the current state of democracy that is so widely held that mainstream politicians would be unwise to dismiss it easily: "Well, I don't think it's working very well, Jeremy", he told Paxman, "given that the planet is being destroyed, given that there is economic disparity of a huge degree. What are you saying, there's no alternative? There's no alternative? Just this system?"

The disenfranchised young of Britain, who are largely uninterested in the main three parties and yet are dismissive of the anachronistic barstool nationalists, felt they had found their spokesman.

chris cummins

So Brand might not have the all the answers but he seems very good at articulating the problems. And that was exactly what he did at the UN headquarters in Vienna, engaging in some slapstick comedy with an embarrassed journalist who was struggling with a microphone: ("What are you doing down there, mate?"), before dissecting the problem with a failing global drugs policy with succinct logic and clarity:

"Drug addicts do not care about the legal status of the drugs they are taking. Drug addicts will take drugs under any circumstances. All that legislation can achieve is a more punitive, negative, pejorative, damning context within which the inevitable use of drugs can take place."

His argument is that people will take drugs. Some will take them for the sheer pleasure of it. And as long as they don't harm anyone else in the process, Brand argues, that is their "human right".

"Drug Use Is Inevitable"

Others, he argues, take drugs to address "some emotional and spiritual problems" and it is unlikely that criminalising these people will create a supportive atmosphere that would enable them to stop. So if drugs use is inevitable, argues Brand, we need to create an environment where drug use can be done as healthily, as safely and with as little damaging consequences as possible." In a nutshell, we need to perceive drug use as a health issue not a moral issue.

chris cummins

Drug taking is rarely good for you from a health perspective, but is not "evil", argues Brand, and its criminalisation has filled our jails needlessly and created something that could justifiably be describes as evil: an organised crime wave with global reach that results in hundreds of violent deaths every year.

"There's literally no reason to proceed with this experiment of prohibition, which has lasted for a century, and that has done nothing but bring death, suffering, crime, create a negative economy", he said.

A New Approach

Brand feels his views are vindicated by the experts he'd met at the meeting in Vienna. He'd met officials from Portugal where a relatively liberal drugs policy has seen the HIV rates among users drop dramatically. Brand says that he spoke to a Swiss policeman who told him that "even from a conservative perspective the penalisation and prosecution of drug addicts simply doesn't make sense." Now, with the prohibition of drugs, fuelling ever more murders across Central America, Brand is calling for an alternative approach of consciousness.

He dismisses the concept of a war on drugs: "You can't declare war on an inanimate object."

We are currently seeing a shift in the growing debate over drug legalisation. Uruguay and parts of the USA have recently decriminalised cannabis. But even ardent proponents of those controversial policies might be shocked by Brand's vision of a world in which all drugs are legalised, including highly addictive Class A opiates such as heroin. "I think we should legalise and regulate all of the drugs", he says. "That's what I think should happen globally as quickly as possible."

Can Heroin Ever Be Safe?

Even recognising the violence fuelled by the illegal drug trade, can legalisation of all drugs be the answer? Isn't it part of a responsible state's duty to try and deter people from poisoning themselves? Addicts say that once you've tried heroin it is almost impossible to permanently kick the habit. I asked Brand whether he thought anyone could take heroin in a "safe" fashion? "I can't mate, I go nuts", came the reply. "But I think some people can."

Many disagree with that assessment. Antonio Maria Costa, who was then executive director of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Drugs, put it in 2010 "Drugs are not dangerous because they are illegal: they are illegal because they are dangerous to health." It is true that current drug policy is failing but Costa has argued that those who argue we should decriminalise the trade in narcotics were "blind to the catastrophic consequences."

chris cummins

Official thinking at the UN hasn't changed greatly since then. Last week, the Vienna-based International Narcotics Control Board criticised Uruguay's move to legalise cannabis for not being compatible with the "letter and spirit" of international drug control conventions.

So did Brand believe that his appearance would change anything? Did he believe that the UN official he had met had taken him seriously? Ever the iconoclast, he refused to honour his hosts:

"It doesn't matter what happens here, mate. I ain't talking to these people. I'm talking to the people of the world. This is meaningless. This is going to evaporate very soon."

Celebrity star dust only goes so far.