Erstellt am: 31. 5. 2013 - 19:00 Uhr

The Science of Superlatives

“You don’t need to be Stephen Hawking or Peter Higgs to have a very interesting, exciting and useful career in science, technology and engineering”, says Mick Storr, the head of teaching at CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research, in Geneva. Nor do you have to be a particle physicist to get a kick out of visiting CERN, which is what I did this week.

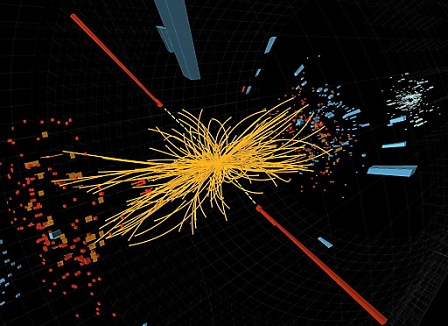

EPA/CERN

Of all the news headlines over the years, the one about the discovery of the Higgs Boson was, to my mind, one of the coolest. More precisely, and scientists tend to be very strict about being precise, scientists at CERN working at the Large Hadron Collider have found a particle which they are pretty (but not absolutely) sure is a Higgs Boson, which is theorised as the means by which particles get their mass. If confirmed, this would stand out as one of the great scientific achievements of the 21st Century so far.

Arriving at the main site of CERN, just next to the border between Switzerland and France, my first impression was that it looked like an upmarket industrial park.

J. Bostock

There are lots of different office-type buildings, roads, grass and trees. But wandering around one soon sees small landmarks that indicate what this place is all about. There is a restaurant with an outside terrace, from which you look out onto a section of blue pipe mounted like a sculpture and displaying the slogan “Accelerating Science” – a reference to the Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, the world's largest and most powerful particle accelerator. There are also weird looking “sculptures” on display which turn out to be pieces of equipment from past physics experiments.

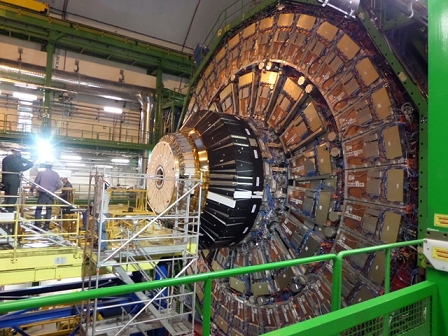

The highlight of my visit was getting to see one of the detectors involved in the search for the Higgs Boson. The LHC is used (among other things) in the search for the Higgs Boson by smashing together two beams of protons at close to light-speed. There are two experiments at CERN looking for the Higgs Boson: CMS and ATLAS. The detectors are the machines which record what happens when the protons collide, and they are huge. I visited the CMS detector, which is 21 metres long, 15 metres wide and 15 metres high and which weighs 12,500 tonnes. As physicist Michael Hoch, who was my guide for the day, explained, the smaller the thing you are looking for is, the bigger the instrument you need to see it has to be, so if you're looking for sub-atomic particles...

J. Bostock

The machine itself is awe-inspiring and somehow beautiful with all its coloured wiring, shiny metal parts and intricate symmetry. The awe stems in part from knowing that you are standing right next to a piece of superlative scientific hardware that has been part of the quest for answers to some of the most fundamental questions of our existence. But it’s also just mind-boggling to contemplate the complexity of this thing and the scale of human achievement in designing, building and operating it. Austin Ball, the Technical Coordinator at the CMS experiment told me that it’s not possible for any one person to have the complete overview, and that the project is built up as a series of layers, with each layer being the responsibility of sub-projects. “It has to be that way because there are a hundred million electronic channels in this thing.”

J. Bostock

The CMS experiment is one of the largest international scientific collaborations in history, involving 4300 particle physicists, engineers, technicians, students and support staff from 179 universities and institutes in 41 countries, including the Institute for High Energy Physics of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

J.Bostock

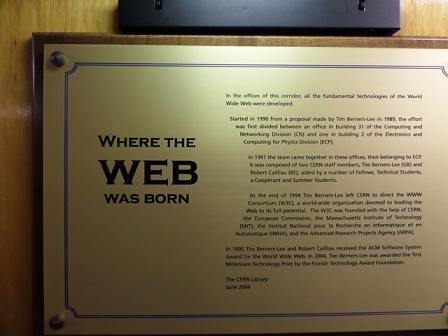

Another historical landmark on my visit was the office once used by Tim Berners-Lee, the British scientist who in 1989 came up with the idea of the World Wide Web. Mick Storr, who worked with him and showed me the door to the office. He told me that Tim Berners-Lee drew a diagram of his idea and gave it to his supervisor, who read it and gave it back with a three word note written on it: “Vague, but interesting”. It illustrates the CERN academic environment which encourages new ideas and allows young scientists to try them out.

J.Bostock

J. Bostock

This international mix of people is another thing that’s special about CERN. In the restaurant I spoke to three Palestinians and encountered people from Greece, Japan, the United States, England, Ireland, Germany, Bulgaria, and India. And that was at a relatively quiet time. “CERN is an international organisation that definitely does work” says Mick Storr, “and you get people working together at CERN who in other circumstances would not really be talking to each other.” It’s the science which brings people together to work on a common goal. Mick also stresses the fact that CERN needs all sorts of experts besides physicists. The theorists come up with the ideas, “but then people have to go away and say how can we test this model? what is it that we can measure? how can we find it? what can we build to do it?” It takes a huge number of people in many, many disciplines.” Mick’s message to those still contemplating future studies and careers is direct: “You CAN be involved, you CAN do it, there IS a place for you”. Austrian students might be interested to know that the Science Ministry sponsors placements at CERN for 10 doctoral students a year.