Erstellt am: 11. 4. 2012 - 15:27 Uhr

A Viennese River of Sex

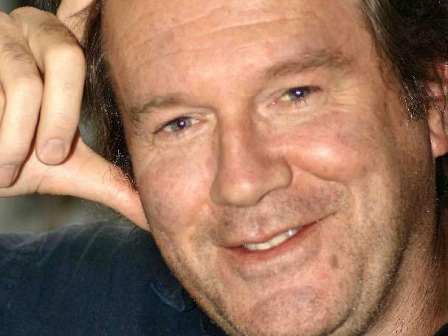

"The theory is that we became modern during the trauma of the First World War," says William Boyd, "but all the ingredients of our modern personalities and our modern sensibilities were there in Vienna in 1913." Pre-WW1 Vienna, says the Ghanaian-born British writer was "probably the most interesting city on the planet at the time."

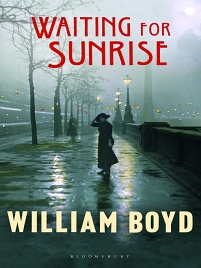

William Boyd: Waiting for Sunrise. Bloomsbury 2012

William Boyd: Eine große Zeit. Aus dem Englischen von Patricia Klobusiczky. Berlin Verlag 2012

Before the cataclysm of World War One, new approaches to art, morality and philosophy were sweeping from the city outwards into the rest of Europe. A whole new consciousness was being created and Vienna was the epicentre

Then came the horror of the mechanized trench warfare killing, which ultimately jolted us for good out of those comforting pre war centainties and western man was plunged into the gloomy ambiguities of modernity. So, Boyd says, Vienna was the perfect city to choose to set 11th novel, "Waiting for Sunrise": "By an accident of history it seemed to contain all those essential elements that made us modern human beings."

Wikicommons/Longmire

Boyd, who also works as a screen writer, director and art critic, is one of the most respected writers. It's his ability to create an atmosphere that first drew me to his work. His first novel, A Good Man in Africa, which was eventually made into a film starring Sean Connery, evokes the atmosphere of a West African diplomatic backwater so perfectly that you can smell the charcoal braziers and hibiscus. You almost sweat under the tropical humidity. Boyd creates worlds that you can live in. I am a fan. When I heard he had written about Austria's capital in a former age, I was eager to take this journey back in time.

Genteel conversation and sexual untertones

Boyd's Vienna is a city of genteel conversation and dark sexual undertones. A young British actor called Lysander Rief arrives in a city where beneath the genteel veneer, a "river of sex" courses strongly. In the prim Pension Kriwanek the landlady uses only two adjectives - "pleasant" and "nice" - but her clumsy, shy maid Traudl prostitutes herself to the residents. It's a city dominated by the new subversive, highly-sexual works of the figurative artists and of course, it is the city of the psychoanalysts, the subject of David Cronenberg's recent film A Dangerous Method. (You know: the one in which Keira Knightly gets spanked.)

Bloomsbury

That's why the "almost handsome" Lysander is in town. He suffers from the embarrassing inability to reach orgasm, apparently linked to a childhood lie that he told (there are echoes of Ian McEwan's Atonement here), and so he comes to the city looking for enlightenment on the leather couch of one of Freud's errant disciples, Dr. Bensimon.

He gets more than he bargains for when he meets a highly strung, drug-addicted sculptress called Hettie in the psychoanalyst's waiting room. She cures him of his orgasm problem (in a big way) and takes him on a journey of sexual discovery, but the affair leads to a false accusation of rape and, subsequently, to a debt to the British government which he can only repay by entering the murky world of WWI espionage.

The title "Waiting For Sunrise" refers to Lysander's fruitless quest for illumination in a world that offers up only more questions and more shadows than clarity in a world of lies and half-truths. The mysteries of the subconcious are superceded by the cloak and dagger world of an international spy and then by the sheer incomprehensibility of a futile war. After opening in the optimism of Vienna's "lemony sunshine" the novel ends on a gloomy, dark, rain-battered day in London in 1915 with Lysander resigned to a world with no easy answers.

Lysander witnesses the new disorientating world of senseless mass destruction in detail, firstly during a foray in the trenches on the Western Front, and then in all its horrifying logistical banality at the War Offices, where "armies are like cities". It's a giddying ride and Lysander has a front-seat: "Time was on the move in this modern world, fast as a thoroughbred racehorse, galloping onwards," the third-person narrator notes late in the book, "and everything was changing as a result."

So there are big themes to explore, but also a rip-roaring yarn. A winner of multiple literary awards and a nominee for the prestigious Booker Prize, Boyd, who turned 60 in March, has no problems with framing his ideas in a page-turner.

Questions of Duplicity and Betrayal

"I have always done it," he said, reminding me that Dickens' last publication was a detective novel. "I have always chosen a genre to provide an engine, a dynamo to drive the narrative on. I write strong, complicated narratives and if you write that sort of novel, things have to happen." He cites Graham Greene and Joseph Conrad, but it may be John Le Carré, who's back in fashion after last year's cinematic adaptation of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, who seems the best model for the use of espionage thrillers to explore character.

"The thing about the spy novel that appeals to me is that it deals with questions of identity and changes of identity," Boyd told me. The nature of espionage means that a spy has to become somebody else, reinventing his or her personality and hiding things away. "So you are dealing with questions of duplicity and betrayal, bad faith and disguise," Boyd continued. "These are very powerful human emotions. In a way, the spy novel gives you the opportunities to explore aspects of our own lives in a way that perhaps a more orthodox novel doesn't. It's an immensely attractive genre."

A boiling ferment of Modernism

We have a lot of fun, too, in the sexy Vienna of the early sections. "You think of the historical period and you think of the empire and this ancient emperor, but underneath it, all was a kind of boiling ferment of modernism," says Boyd, "and that modernism carried on to the way people related to each other. Their personal lives were as intense and unusual as the art they were producing." The siren Hettie dresses boyishly and has penchant for pantaloons and broaches. Her partner Udo Hoff, a broad-shouldered man who rails about the empty fakery of the Ringstraße, shaves his head like Kokoschka. Boyd goes into great detail in describing the sartorial eccentricities of his characters.

"You'd be surprised by how extravagant people were," he told me. "Hettie's clothes are very typical of an artistic and bohemian type." She wears tight-fitting little jackets and hats, and has little tinkling bells on her shoes. "That's the sort of detail I seized upon when I was researching the clothes of the time, because it makes Hettie seem alive."

flickr/huffstutterrobertl

As in previous Boyd novels, notably his 2002 "Any Human Heart", historical characters make cameo appearances: We meet a distinguished but dismissive Freud in the Café Landtmann, and a man who might be a faintly ridiculous early Hitler, raising a rabble from a soap box.

Given the vivid details in the narrative, it is surprising to learn that the soft-spoken Boyd had only visited Vienna for three short trips while researching the novel, and had never been here before writing his 1995 short story "The Transfigured Night". But the city had long haunted his imagination, he said, particularly the early years of the 20th century, "when the old world ended and the new world - our world - began". While researching "Waiting for Sunrise", he spent hours studying old street maps and guide-books, trying to imagine the feel of the pre-war city. A voracious reader, he devoured every book he could find, fact or fiction, about that episode of Viennese life.

Boyd particularly highlights two works for insight into the atmosphere of the final months of the Habsburg era: Robert Musil's 1,000-page novel "The Man Without Qualities", which he describes as "Vienna's Ulysses," and Joseph Roth's "The Radetzky March", which he describes as a "true European masterpiece," whose atmosphere is "so stifling, the thunder has to strike." It's the perfect diagnosis of Vienna in 1913.

Boyd's novel won't be to everyone's taste. A lot of ideas and events are packed into few pages and the various plot twists and scene changes come at a price. There are, perhaps, a few too many coincidences and contrivances. But as a high-brow time-travel adventure into a city that has lost its cultural pre-eminence but not, I think, its sexiness - it is well worth the roller coaster ride.