Erstellt am: 19. 7. 2011 - 16:44 Uhr

God in Africa

I was in a suburb of Accra, sitting in a "spot bar"called Generation Game, a thatched concrete compound on the edge of a dirt road that led down to the Gulf of Guinea. I was drinking beer served in three-quarter litre bottles when my neighbour Pepsi asked the question that is the biggest mark of new friendship in Ghana.

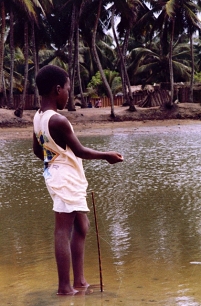

Nzulezo Stilt Village - Travel in Rural Ghana

“Will you come to church with me on Sunday?”

I was touched and said yes immediately although I hadn't been inside a European church in years.

Religious Boom

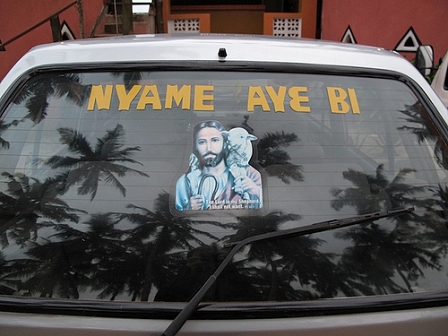

Being asked to church is a sign of affection and trust. It would be really rude to refuse. Religion pervades all parts of Ghanaian life. The public buses are adorned with pious slogans like “Jesus Loves You” and there are barber shops called "God is Good Hairstyling." Almost all secondary schools are church-based. People won’t ask you if you are a believer, they’ll just assume that you are.

flickr.com/neate

There never seemed to me to be any point in creating a pointless scene by questioning the consoling certainties of religion in a country where many of my friends had lost a brother or sister to childhood illness. Who wants to be a Clever Dick? Being agnostic seemed like a luxury. And, of course, I was curious. Time after time total strangers had helped me out. I tried to reward them - often crassly getting out my wallet. Almost always they cut me off, explaining away their kindnesses with the words "I`m a Christian". I had been deeply impressed. I thought religion in Africa might be something eye-opening for me.

The Church

Pepsi was a barrel-chested 20-year old who did a variety of odd jobs to get by in life in the busy Teshi-Nungua suburb. He told me to meet him outside the bar at 7 in the morning on Sunday and then we`d walk together to his church . I was nervous of being late and ruining my friend`s day so I was already there at 6.30 leaning against the concrete walls of the deserted bar and staring at the goats nibbling among the discarded rinds of water melon. Pepsi himself turned up sometime around 8 with a big smile, a hug and no explanation.

Gone to Dogon Star gazing in Mali

We crossed the main coastal road in a sprint and then wandered into the sandy roads of the Nungua neighbourhood where sprawling slums backed into elegant residential streets. After about five minutes we came to a large hall like building that was set back from the road and fronted with a great rarity - a lawn still vaguely green that was fronted with a low white wall.

There was a sign outside reading “The Christ Will Triumph Church” and dozens of people were trooping inside. The room was already mostly full of men wearing starched collars and women in colourful wraps; all of them sitting in row upon row of foldable chairs.

chris cummins

At the front of the hall there was a small stage fitted with a microphone and behind it was a larger stage with a six-piece band, complete with guitars and drums. Pepsi took me by the hand and guided us to a couple of spare seats in the middle of the left aisle.

Warming Up

The band fired up with some swing highlife music as a preacher arrived and we all stood up. Everyone started swinging with the music and I wobbled self-consciously. The preacher was around forty with a moustache. He had powerful shoulders but a paunch belly. He picked up the microphone, bent over towards the ground and then slowly raising himself shrieked “In the NAME of Jesus.” The band kept playing swinging highlife in the background and the congregation started marching on the spot as the preacher bent double again and raised himself shouting even louder “In the NAAAAMMME of Jesus.”

He was the warm up act. He kept repeating the phrase over and over again, ever quicker, until he was hoarse and seemed in danger of hyperventilating and the congregation kept marching on the spot, and the band kept playing and some of the faithful started gesticulating as if arguing with an invisible interlocutor. As I was growing up in England, religion had meant going to Church at Christmas and Easter in cold draughty stone buildings where we’d politely mumble along to the prayers and hymns. This was a new world. The trance like opening seemed fun and disconcerting at the same time - a form of organised madness.

Then the preacher withdrew and the band struck up an even jauntier tune and everyone started dancing between the seats and in the aisle, smiling at each other and even hugging. Some of the church-goers sang. One large expensively-robed woman began to sing a powerful song that was much slower than the rhythm of the music should have allowed. Other people, seemingly overcome with the Holy Spirit, literally fell to the ground, rising slowly and looking dazed.

By now I`d stopped enjoying it. I didn’t get it at all. I couldn’t really understand what was going on. I just wasn’t feeling it. It was like being the sober designated driver at a party that had got out of control.

I knew how the people in this district of Accra lived - long working hours 6 days a week and a confined family life with little free cash for leisure or few freedoms. I wondered whether they looked forward to the chance to losing their inhibitions on Sunday morning the way that desk-bound office workers look forward to dancing Saturday night away in the night club. Was it just another way to lose yourself in the ecstasy of music? I looked around at the contorted faces of the enraptured faithful mouthing words as though they were really “speaking in tongues”. It suddenly seemed grotesque.

The Sermon

Then came the shock - a colossal white woman arrived, dressed in pseudo-African robes. Her fleshy wrists were jangling with bracelets. The preacher, it seemed, was a Canadian woman.

She stomped up and down the aisle and launched a seething sermon about sin and laziness and how God was disappointed with the entire congregation. Her face was red with fury as she spat out her words, asking “What have YOU done for God this week” like a perversion of the JFK speech on patriotism.

By now I was furious too. What right did this self-inflated red faced woman have to come here and insult the hard-working honest people of Teshi-Nungua and threaten them with gothic visions of perdition? And the sermon wouldn’t end. The fire and brimstone ranting went on into a second hour; the whole Church service was into its fourth hour. The preacher was sweating profusely; large damp patches were forming on her part of her robe beneath the chubby white arms.

What did she get out of it? Was it an ego trip? Was it money? Did she really want to save lost African souls like a missionary left over from the 19th century?

Indeed money became her next theme. Specific sums were mentioned for the atonement of the sins of the past week and they were massive sums in a city where much of the population survived on the equivalent of around 2 dollars a day.

I just felt sick and wanted to leave but I knew I would mortally offend Pepsi. When we were finally released - blinking into the blinding lunchtime light - he turned to me enthusiastically.

“How did you like it?” Pepsi asked, smiling as he shielded his eyes from the sun with his hand.

“Oh, yeah, it was… great. Thanks for taking me.”

I mean, where do you start?

Coming Down

I felt depressed and confused. The service had seemed to me like a cathartic piece of escapism for the congregation and an absolute racquet for the church – a piece of bullying, money-making hypocrisy. Maybe I had gone to a rogue church. There were hundreds of others in Accra alone. But I wasn’t going to spend every Sunday finding out if the rest were different.

I wandered back across the coastal road and went to the bar where I sat alone rolling a beer bottle between my hands. An impressively dread-locked Rastafarian called Bo, who lived opposite the bar, was sitting on his doorstep wearing his knitted shoes which were green, red and yellow in deference to Ethiopia - the Rasta homeland. He called over to me and invited me into his hut for one our impromptu lessons in drumming.

I never made any progress in these lessons, neither in matters of rhythmn nor technique. But it didn't seem to matter. I`d bash ineffectively with curled fingers on the tight drum skin and he`d give me gentle advice while improvising lyrics in his soft voice that circled around three ever-repeating themes: Jah was all powerful, we should thank him and we should love each other.

chris cummins

I`d heard these simplistic Rastafarian mantras in reggae songs and alternative European bars. The words always sounded empty and insincere to me. But here I liked them as we sat on the carefully swept floor of this little concrete hut - just a single room bare of anything but a sleeping mat, a mosquito net and a bamboo broom. Coming from a gentle gap-teethed man in a knitted hat, the lyrics seemed innocent and somehow beautiful after the visions of hell that I`d heard in the morning.

Feeling better, I decided to walk down to the sea to clear my head. I got up and took my leave “It seems there`s a lot of God around today,” I said, heading off down the pot-holed road towards the beach.

“Everyday much Jah,” nooded Bo in agreement, waving lethargically after me.

*some names have been changed.