Erstellt am: 17. 7. 2011 - 07:57 Uhr

Gone to Dogon

I discovered the universe for the first time because I desperately needed a pee.

It was the middle of the night and I was wide awake lying on my back in a sleeping sheet on the roof of a dusty rooftop of a Malian village on the edge of the Sahara, trying to distract my thoughts from my bladder. I was unable to sum up the courage crossing the uneven and dusty roof top negotiating my way down a wooden rickety ladder to relieve myself. So all I could do was cross my legs and stare up at the night sky. It was so dense with stars that it looked as if someone had thrown a bag of white sparkly dust over the sparse heavens that I knew from over-lit Europe.

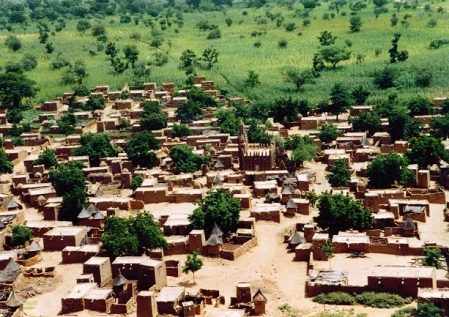

This was the Bandiagara escarpment, home to the Dogon people who live in small villages with minimal electricity. They are among the most distinctive and celebrated African ethnic groups and have lived apart from mainstream Malian culture for centuries. They area is famous for its night skies. When European anthropologists first began studying the Dogon people back in the 1930s, they were amazed at the cosmological knowledge of these rural people who knew of stars thought to have been only recently “discovered” by western telescopes. All the Dogon had had to do is lie on their backs and look.

chris cummins

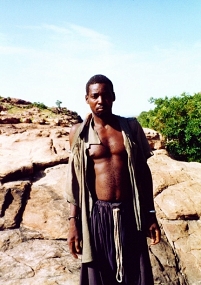

To access this enchanting pocket of the Sahel, I`d picked up a local guide, a doll-face gangly teenager called Hassimi, at the nearby river Niger port Mopti. I travelled with him and returning villagers on the back of a jolting pick-up through a landscape of acacia trees, scattered rocks and the occasional termite mounds until an enormous ridge of yellow pot-marked rock – the Bandiagara escarpment.

The French ethnographer Marcel Griaule’s mid-20th century reports of his encounters with the Dogon were so evocative and so colourful that the Bandiagara escarpment has become a well-known target for the more adventurous backpackers and anthropology students. In the past decades the poverty-stricken locals have been able to etch out incomes from this trickle of tourists, although not enough, it seems, to give them adequate healthcare education facilities.

chris cummins

Hassimi was my sort of living letter of introduction. He’d arranged for your food and accommodation among his relatives and friends who lived in the string of sandstone villages that lined the foot of the cliff face. After my night of star-gazing, he led us down tracks that followed a narrow river where women washed colourful wraps of clothing. A flea-bitten donkey reluctantly dragged our bags and supplies on a cart whose wheels dragged deeply through the red sand of the country road.

Long Greetings

See also: Nzulezo Stilt Village Travel in Rural Ghana. Is tourism helping rural poor areas?

Every time Hassimi met someone en route, a series of melodic greetings were exchanged, with the oldest person of the two starting the conversation.

Roughly, the greeting translates to “How are you? How is your father? How are the children? How is the house? How is the village?” It is pure formality since all responses are that things are “fine.”

chris cummins

“What if you no longer have a grandma?” I asked Hassimi.

“Oh you just say they are fine anyway,” he replied, smiling his gentle smile.

We set off early and it was so hot by ten in the morning that we soon hid in shade of thatched communal courtyard of small partially walled in village on the route, sipping endless rounds of sweet peppermint tea until I summed up to energy to look around. There was a skinned goat covered in flies hanging outside a butcher’s shop and there was a stick and mud mosque, which surprised me at first. The Dogon had settled in these parts after fleeing northern Ghana and the prospect of forced conversion to Islam centuries ago. But now although most of the Dogon are “animist,” about a third of the people have converted to Islam, and there are even a few Christians.

chris cummins

Just before dusk we arrived in another village. It was made up of a few flat-roofed houses arranged in a series of compounds. We entered ours by climbing over a small wooden ladder. On the other side was a white-sanded courtyard where women were preparing food over charcoal fires and other members of Hassimi’s extended family were sitting around, lolling in the late afternoon sun.

Life in a Dogon Village

It was hard to work out the relationships. Here, family units have a complicated structure. I had learned in a guide book that a Dogon wife stays with her father until she has had her third child, sleeping with her husband during the night but returning to her father’s house during the day. None of the houses had windows, which kept it cool but also dingy and dusty inside. My eyes, having spent hours in the blinding light of the Sahel, were slow to adjust, and I could make out little else but the voices and a few shadowy outlines.

Among the compounds there were granaries - bee-hive shaped buildings topped with a witch’s hat of straw and beyond the village, donkeys grazed in the shade of wiry trees. By the compound’s western wall, village boys were furiously playing football on a dusty pitch as the sun set behind them.

The sand at sunset looked blood red and the footballers kicked it up in clouds of pink. Having attached my mosquito net to a clothes line, I was sitting on my roof with reptile-like immobility. But the footballer’s outbursts of energy reminded me how hungry I was, so I climbed down a rickety wooden ladder to a dinner out of the communal couscous and stew pot.

chris cummins

The next day, after a brief stifling-hot walk to the next village along the escarpment, I met a traditional the village chief, the hogon. We had to climb up part way into the cliff face to meet him. He was dozing on a wooden chair when we met arrived, surrounded by cave-like dwellings. According to Hassimi, the chief spent all his time in this lonely perch. The villagers climb up to him to solve their problems, which he tackles by sacrificing animals. He was very old and very thin and he told us the history of the cave-like dwellings around him. Or at least his version of that history.

Legends of the magic finger

They had, he said, belonged to a pygmy-sized people called the Tellem, who had been defeated and evicted when the Dogon discovered they could kill off the little cliff-dwellers by simply touching them on the forehead. It was a more colourful and interesting story than the more prosaic explanation of battle and exile that I had read in the guide book. I chose to believe it.

To help me understand, Hassimi illustrated his translation of the hogon’s words by jabbing me above the eyes with a dirty finger. So the unfortunate Tellem are gone but their legacy remains in the mysterious cave-like terracotta-coloured homes in the cliff.

Tourism is a double-edged sword for areas like this. The revenue is more than welcome. But the hogon has to spend more time performing this potted history for disbelieving paying-guests than in advising his villagers. And at one busy village, there was the rather disturbing sight of a hunter, dressed up in the traditional garb, posing with a small bewildered-looking child in front of a firing-squad of tourists with flash cameras.

chris cummins

But most villages were quiet and I could genuinely interact with the locals. We spend our penultimate night in a nearby village in a house where Hassimi’s young cousins lived. We sat around listened to Bob Marley on a battle-worn ghetto blaster while the cousins excitedly caught up with news and gossip from Hassimi’s trip to Mopti. At sundown we went with some boys from the village to a well that was in the current of some waterfalls that cascaded threw a boulder strewn gulley. I swam against the current with the boys and we dared each other to jump from ever higher rocks and played underwater tag.

That night a storm came. A crack of thunder woke us from our sleep and we had to rush down from our rooftop and take refuge in one of the windowless chambers – places with the air quality of a coal shed. In the morning rows of newly formed waterfalls were tumbling over the sheer cliff-face of the escarpment and the reinvigorated grassland below seemed to sing with insects. As we returned for a morning swim, the waterfalls were almost beyond recognition. The pools were now deep and the flow was fast and rich.

On top of the rock

On the last night we climbed up to a village perched on top of the Bandiagara escarpment – one of the Kondou villages. From the foot of the cliff, the path snaked perilously upwards, threading for an hour and a half through towering pillars of eroded rock. The village was perched on the corner of the ridge. The buildings, populated by herders, had been built straight onto the bare rock of the plateau and on three sides there were spectacular views over the lower plains. From high above they looked surprisingly green, with the bushes that had looked sparse from ground level now looking densely packed and stretching out as far as the horizon.

chris cummins

Up in the barren landscape of the village, huge, docile bulls stood tethered to rocks. With mournful eyes they watched the village women trek to and fro with buckets of water on their heads, while small boys guided herds of goats down steep, rocky pathways.

Grunting and indignant, dirty pink pigs were penned up in stone enclosures. Behind the village – the only direction that didn’t end in a sheer drop – was some green land and then another column of rock from which two waterfalls fell. One waterfall was the shower for the men, another for the women.

Dumbfounded by the beauty, I hardly spoke as I sipped bitter millet beer out of plastic cups handed out by my hosts. The night was coal-black and there was a warm evening breeze and I sat there drinking the warm, grainy brew feeling like Galileo without a telescope.