Erstellt am: 7. 7. 2011 - 13:06 Uhr

Nzulezo Stilt Village - Travel in Rural Ghana

The idea of visiting a village built entirely on stilts seemed so utterly National Geographic that I had to make the trip.

Trunks of raffia trees prop Nzulezo, a Ghanaian village near the border with the Ivory Coast, above the dark waters of Tadane Lake just a few kilometres inland from the Gulf of Guinea. The village was settled by a people that had fled to the coast from the distant inland of the Sahel hundreds of years ago, reasoning that although they were traditionally farmers, living on a lake would give them the security from the invasions that had blighted their lives in the north. The village, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage site since 2000, has become part of Ghana`s drive in promoting rural tourism - a way to spread the growing prosperity to all corners of the country.

You can visit, but you’ll probably have to drink homemade gin with the village chief.

xxx

Getting there from the capital Accra meant taking a ride to the industrial city of Takoradi-Sekondi on one of the over-filled minibuses known as tro-tros that serve as the heart of the public transport system in Ghana, and then changing on to a second tro-tro for the last 90 kilometres to a tiny coastal village called Beyin: the gateway to the lagoon in which the stilt village of Nzulelo sits.

The tro-tro to Beyin was already full when I tried to get on but in Africa this rarely matters; everyone squeezes up and the driver gets another fare.

As we approached the village, being off the beaten track took a literal form - the last few kilometres of road were unpaved and so beaten up and uneven that our top-heavy bus rocked dangerously like a boat caught in a deep ocean swell.

The van was overloaded with the provisions that the villagers were bringing back from their trip to Takoradi, the regional trading centre, and, alarmingly, these included a giant plastic drum that doubled the height of the bus. Several times I was sure that we were going to tilt over but the African passengers seemed hardly to notice, staring straight forward, their eyes fixed on the dreamy middle distance, the portrait of perfect calm.

At one point we had to stop for petrol at a station with a hand-powered pump. I got out to relieve my legs from the growing cramp and was surrounded by smiling children. One very small boy started pulling at my very white leg hair with a look of wonder on his face. A skinny old man wearing a string vest was wandering around carrying an enormous tea-pot. He waved shouting out "Hello Obruni!" using the local Fante word for white man.

By the time we got to the village of Beyin such a complete darkness had fallen that I couldn’t see a thing. The village was entirely without electricity. The only light came from a few charcoal braziers, roasting potatoes on peanut oil, and the whites of people’s eyes or teeth. The glow coming from the stove of a woman selling rice and fish illuminated a huddle of children waiting in hungry anticipation. Another child - children often seemed to run the country - guided me to the only accommodation in the village. It was easy to find because in the dark night it was the brightest building - a little square castle on the sea front called Fort Apollonia. It had clearly been white-washed once, like all the castles on the coast, but the last application of paint must have been several years back and now it was grey and speckled.

The fact that it was a former slaving castle, one of 14 in Ghana, should probably have made me feel morally queasy, particularly as a Brit. But, to be honest, it didn’t. I was excited to be staying in a castle, where you had to draw water from a well in the courtyard, walk around with a battery-powered lantern for want of electricity. From the ramparts you could listen to the sea hitting the rocks and watch the foam lit up by the moonlight.

I told the old man at the castle`s reception that I wanted to go to the stilt village and, the next morning, as I was having a breakfast of scrambled egg and sweet bread at a street stall, a muscular guy with a shaved head came up, introduced himself as Kwamin and saying he was originally from Nzulezo and that he`d take me there.

I grabbed my things and trekked out with our guide to where the canoes were moored, walking on a dark muddy path and occasionally wading through small streams, brushing my legs off fiercely afterwards for fear of the snail-like bilharzia parasites said to lurk here - a dangerous infection transmitted by snails in slow-moving water.

The undergrowth was very green and Kwamin said black and white Columbus monkeys lived in the trees but I saw no sign of them. The clay path under our feet wasn’t red as usual in Ghana but a sort of viscous black clay that felt sticky underfoot.

We came to the banks on a lagoon where some narrow pirogues were half drawn up the flat muddy bank. Kwamin untied one and pushed it into the water. I waded in after it and tentatively lowered myself in the front of the boat. It rocked steeply to the side letting in a slop brown water, but Kwamin slipped on at the bow with hardly a sound and no splash.

He picked up a long paddle that had lain near the canoe and started pushing us slowly out across the water. There was a small lake dotted with water lilies and surrounded by coconut palms and then we cut into a narrow channel through the jungle where thick foliage curled overhead and was reflected in the perfectly still water. When we came through the tunnel of trees, we were back out in the open, unprotected from the fierce morning sun. We headed through a channel that had been cut through reeds that were bright yellow in the sun. The water was black as oil. After the insect cacophony of the brief stretch of jungle it was quiet out on the lagoon with just the soft sound of my guide's paddle entering into the water in a languid rhythm.

After a while we met another canoe punting in the other direction softly parting the black channel. Its two passengers staring at us with a mixture of disinterest and mild suspicion as the two vessels slipped by but mumbling apparent greetings in tribal African to Kwamin.

The channel led to a broad river, the Amanzuri, which in turn soon flowed into a large brown lake at the shores of which we got our first glimpse of the stilt village. It looked tiny in the distant, it`s home to only around 600 people living at close quarters, but as we got closer it looked more impressive and almost South-East Asian looking with a series of large one story buildings jutting out over the still dark water like boat houses at a rowing club.

chris cummins

The village had a charming hap-hazard feel; each building was a slightly different size and shape as was made from the trunks and larger branches of the local raffia trees. The wood was simply tied together and the dwellings are being constantly rebuilt as the wooden poles rot and new trees are felled to replace them. The effect is that the village is constantly evolving and changing. The trunks weren't wide so to support the weight of the buildings many poles were dug into the bed of the lake giving the houses the look of a many legged insect.

Kwamin slowed the canoe and we clambered up onto the wooden-planked walkways that provided the arteries for the little village. There was a little welcome committee and we drank the local home-brewed gin with the village chief, a fiery clandestine drink that is reputed to have turned people blind. It always comes in old plastic mineral bottles and is one of the most frightening things I know. There were kitchens build separately away from sleeping huts - wood and open fire cooking is a dangerous mixture.

Outside one of the kitchens a woman was making fufu - a backbreaking task that involves using a long wooden stick to pound a mixture of cassava and plantain together until, hours later, it becomes an edible if globular pulp that you eat like dumplings. She saw me watching and invited me to have a go, laughing as I broke into sweat as I clumsily banged away to frustratingly little effect.

xxx

Having looked so small from the water it was amazing how far back the village stretched, always on planked walk-ways until it ended in the multi-hued green of the lakeside jungle. There were colourful rugs hung out to air outside the wooden houses and washing lines spanned the alleyways. Most of the wood was unpainted but one house was blue and another was painted a vivid green and served as a bar. The most surprising thing about the village was that, unlike Beyin, there was electricity here. The village was powered by car batteries which the villagers transported, by boat then bus, to the coastal towns for recharging.

The batteries even powered television sets, antenna were poking up above the wooden huts, and music was playing out of a ghetto blaster. I was searching for my fantasy in the idyll of isolation, they were searching for theirs in western hip-hop and the daily soap operas on Ghanaian television. There was even a small bar. For better or worse, the tourism industry was changing the village. Isolation was no longer what the villagers craved.

As a traveller, you go away from places like this, feeling vaguely uncomfortable. I suppose I didn’t really want to visit a real place, but to fulfil some subconscious desire to visit some ‘authentic’ fantasy land. It`s the dream that ended a long time ago and I knew that but it was still disappointing to get somewhere and discover a bar selling bottles of Coca-Cola. Yet even as I felt that disappointment I knew I had no right to feel that way.

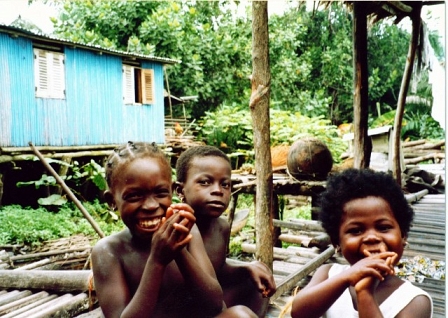

There were children everywhere in Nzulezo. They lounged around or playing tag on the fragile board walk. Or they crowded around me asking for pens or presents. They were gorgeous in the way that all Ghanaian children are; with huge eyes, curled lashes and smiles so wide that their gums show.

chris cummins

But it was hard to interact with these kids in the way that you could with kids in the Ghanaian cities and larger villages. These children had grown up in an odd village that had become a tourist attraction. Their only encounters with westerners were short and one-sided. They were gawped at and then they asked for presents. I chatted, going over the same banalities as we always did with the children, made the same exaggerated play acting - shivering to show how cold it was in my home country, I was desperate to get some sort of relationship going so that the experience could mean something to them as well. And I swore I wouldn't take photos, wouldn't treat them as beautiful tourism attractions. And then, of course, I did. I couldn't help it.

It`s the double-edged sword for a country that has not yet been ruined by tourism. The World Tourism Organisation argues that responsible tourism can play a significant role in eradicating poverty and meeting the millennium development goals in the Third World. That's probably true but it is hard to define 'responsible'. In Ghana, the balance is still there. There are few enough tourists that in the more populated areas I was easily absorbed and made to feel welcome. I was even becoming a bit of an attraction myself - the blond outsider with white hairy legs. I was an oddity but oddity with something to share as well as take.

The rural areas are keen to exploit this money spinner. But it is easy to feel uncomfortable in these small villages. It makes you think of Alex Garland`s sneering narrator Richard as he sums up the backpacker`s motivatons for travel: "Of course witnessing poverty was the first to be ticked off the list." There are no unexplored areas in the 21st century. There is just the responsibility to try and make sure your visit benefits rather than harms the local community. The problem is how to be sure.