Erstellt am: 19. 2. 2010 - 17:00 Uhr

The Age of the Killer Robots

Join Chris Cummins as he takes a discerning look at "The Age of the Killer Robots", this Saturday, as of 12 midday, on FM4's Reality Check.

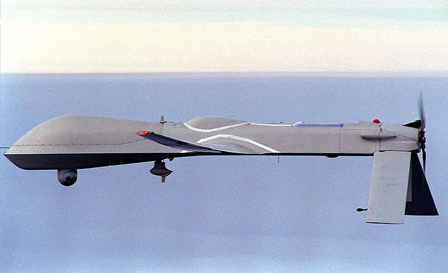

The age of the killer robot is no longer the science-fiction dystopia of James Cameron. It's here already. Thousands of military robots are being used on combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan as we begin to outsource the risks of war. These bots range from giant R2D2 look-alikes called C-RAMs, which are armed with 20mm canons, to the collateral damage prone unmanned 'drone' aircraft, which are often controlled by an office worker 7,500 miles away.

- gemeinfrei -

This revolution in warfare is happening at a dizzying pace, says PW Singer, a former analyst for the Pentagon and the CIA. He's written a book called Wired For War: The Robotics Revolution and Defence in the Twenty-First Century. There were no US ground robots in action when the Iraq began in 2003. Now there are 12,000 carrying out missions that humans used to do. "But this is just the tip of the ice-berg," says Singer. A report by the US Joint Forces Command predicts that autonomous robots will be the norm on the battlefield within 20 years.

And since the rules of engagement can't keep pace with the development, the trend has posed some very worrying practical and ethical concerns that are yet to be adequately addressed.

globalsecurity.org

The advantages of using robots in war are obvious and Singer summarizes them as the "3 Ds". Robots can replace human soldiers in work that is dull - unlike humans their concentration doesn't waver when staring out at desert sands for hours. They can do work that is dirty – for example operating in chemical warfare environments. And most importantly they can do dangerous work – when a robot is destroyed, there is no flag-covered casket ruining public opinion back home or letters to be written to bereaved mothers.

"We're seeing an entirely new experience of war," says Singer. For 5,000 years of human history going to war meant going to a place of such danger that you might never come home again. When you left for battle you knew you might be seeing your family for the last time. But while researching his book Singer met soldiers who dropped bombs on human beings in Afghanistan via a control panel in Nevada and then drove home to have a family supper. He might be killing a militant a 4pm and then be discussing maths homework at 6pm.

It's killing without the risk of being killed but interestingly the office-based gunners often suffer higher rates of combat stress than their fellow soldiers based in Iraq or Afghanistan. Is the switch between the brutality of their job and the safety of domestic life too abrupt? "At the end of the day," suggests Singer "maybe the human psyche isn't set up for all of this?"

It's no coincidence that the control panels for many of these robots and drones look like the control pads of video game consoles. "The military is, in a sense, free-riding off the video game industry," says Singer. That industry has spent tens of millions of dollars on developing a pad that fits easily and comfortably in the hand and is intuitive to use. Why not take advantage of that?

Video game culture has also trained up an entire generation to be expert in using these systems. Singer spoke to a military robots developer who had been working on a machine-gun armed ground robot controlled with what looked like an X-box pad. He told the author that you could hand it to any kid and "he'd figure out how to use it in a couple of moments."

It's no wonder then that one of the US top drone pilots is a 19-year old school dropout who is so good he is training up the rest of the corps. Top Gun, once a six-packed university graduate, now has more in common with a slacker. Poor old Maverick.

But what of the problems? As anyone who has used a GPS satellite-navigation system will know, software can go wrong. And in warfare these glitches can cost lives. C-RAM, actually a tool to counter incoming missiles and mortars, tried to shoot down an incoming US helicopter on his first outing. The original software wasn't sophisticated enough to discern between friend and foe. Old R2D2 just wanted to blow up any airborne object coming his way. "What might be intuitive to humans is something that you have to specifically program a robot to do," says Singer. In what an official report termed as a "software glitch" a South African anti-aircraft robot went berserk on a training mission, firing low in a circle and killing 9 soldiers.

For practical reasons the new generation of killer robots are being trained to be increasingly autonomous. This makes them more effective when militants manage to jam the signal to the controller. In the future, it will also spare personnel. At the moment typically one human soldier controls one robot but with autonomous bots one soldier could be in charge of several.

We are not in Terminator territory yet since they are not programmed with a survival instinct that could cause them to rebel, but what of future generations? It's a worrying enough conundrum for the scientists who started these projects. Many of them are now getting cold feet, comparing themselves to the forefathers of the nuclear bomb who initially failed to envisage the nightmarish implications of their work.

But these self-proclaimed "refuseniks" can't put the lid back on the Pandora's Box that they have opened. Stopping the military robotic revolution would, in the words of Singer that would mean "you'd first have to stop war, capitalism and science."

And there are further ethical problems, aptly summarized by prize-winning British commentator Johann Hari in The Independent: "Robots find it almost impossible to distinguish an apple from a tomato: how will they distinguish a combatant from a civilian? You can't appeal to a robot for mercy; you can't activate its empathy." And what about collateral damage? If a machine malfunctions and drops a bomb on innocent civilians, who should be prosecuted? Who bears responsibility for the harm robots inflict? The person behind the control pad? The programmer? The scientist who developed the software in the first place?

-

Tactically it might be short sighted too. The Bush Administration constantly maintained that the new technology frightened the militants but commentators in the Muslim world have interpreted the trend to send machines to fight humans as an admission of cowardice. "In a war of ideas perceptions can take on a reality," says Singer.

But the main concern must be philosophical. Dead soldiers and grieving mothers are the political consequences of adventurous foreign policy and that has always had a restraining effect. In the UK what seems like a constant stream of funeral corteges headed from the military base is sapping support for the government that instigated the costly war in Afghanistan. Governments are unsurprisingly prepared to spend billions to outsource the business of death to inanimate soldiers.

But if the decision to go to war loses some of it political consequences, what is to rein in rich countries aggression? The political barriers to war are already falling in the West. In most countries conscription has gone and our economies can swallow war without the rationing that our grandparents knew.

These robots mean we can increasingly engage in acts of war without putting "our boys" in harm's way. Johann Hari wonders how long the "systematic slaughter" in Vietnam would have lasted had the war not been so costly in terms of American lives and how many Brits and Americans would protest the Afghan campaign if it were only Afghanis who were dying? PW Singer emphatically concurs: "It makes us view war as costless to us," says Singer, "and might seduce us into wars that we possibly should have avoided."