Erstellt am: 11. 3. 2016 - 15:46 Uhr

Fukushima: A synonym for disaster...

AFP PHOTO / POOL / POOL / KAZUHIRO NOGI

FM4 Reality Check

Listen to the programme in the FM4 Player or subscribe to the podcast and get the whole programme after the show

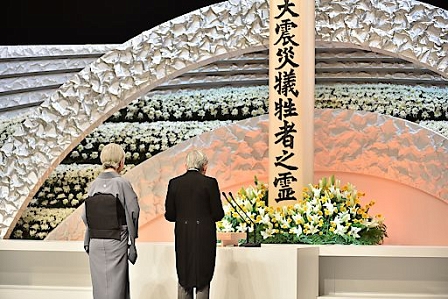

Five years ago, a massive earthquake off the coast of northern Japan unleashed a massive tsunami.

More than 18,000 people were killed, entire villages were laid to waste and power to a nuclear plant was cut off, triggering multiple meltdowns in the world's second-worst nuclear disaster.

It was an event which brought dramatic changes to life in Japan - changes that will be felt for decades to come.

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

Dieses Element ist nicht mehr verfügbar

So what is the situation in Fukushima 5 years on; is real progress being made? Reality Check asked Tokyo-based correspondent, Anna Fifield:

Well, it depends who you ask. If you ask TEPCO, the electricity utility that ran the nuclear plant, they have been talking about how much progress they’ve made and they recently took foreign journalists including myself on a tour of the plant, and were talking about how good things are now, how low the radiation is. But to me, going in for the first time, I was quite shocked at the numbers I was seeing on my Geiger counter, and seeing the villages all around, the area which had not been decontaminated yet. They’re still like ghost towns, and while people are starting to move in to some of these towns, there are still areas which have not been decontaminated and cleared for people to return.

So I imagine there’s still a lot of testing for contamination that is still going on?

They’re testing near the forests round there, the soil, the sea in front of the nuclear plant and they say that they’ve got it all under control and have brought the levels right down, and they have been doing a lot of decontamination work. There’s a few big problems with that though, and that is what do they do with all the stuff that they’re clearing. So at the moment they are pumping huge amounts of water out from underneath the reactors, which are still right there on the waterfront, and ground water is flooding into them. So they’re pumping water out of that that is radioactive and contaminated, thousands and thousands of tons of this every day, and they don’t know what to do with it. So now they’ve built more than a thousand hugs tanks on the site where they’re storing all of this contaminated water. They’re processing it, but they don’t know yet whether they will release it into the sea, whether they’ll try and evaporate it, what exactly will happen with it. It’s a political decision that the politicians in Tokyo will have to make. Also there’s the issue of all the contaminated soil that they’ve been taking out from various places around this region. That’s going in to these huge black plastic sacks which are just lined up in fields in this area, as far as the eye can see. And so they don’t know what to do with any of the stuff yet, they’re just going to continue to store it on the site until they get political direction.

EPA/KIMIMASA MAYAMA

All of this must have had, and still be having, a massive impact of the livelihoods of people – fishermen, farmers?

Yes, very much so. In the immediate area surrounding the nuclear plant people are still not able to live there. You can go past the houses and see the bikes outside and pot plants on window sills that have just been left there for five years. So for those people, for sure, their lives have been completely disrupted.

The thing that people maybe don’t realise is that this disaster had such a huge impact along the entire coast. Fukushima is one area where it was very much a nuclear disaster, but all the way up, and further north up that coast where the tsunami really hit, that area is still completely devastated. I was touring around one of the worst hit areas last week – a town called Rikuzentakata – and 90 percent of the buildings were wiped out by it. Even today that looks like a huge construction site – the whole coast, the sea area is just earth movers and dump trucks and all sorts of construction equipment just building up the land still, there’s not much to be seen there. So it’s very much a long-term process.

Returning to the nuclear industry – all of Japan’s nuclear reactors were shut down for safety checks in the wake of Fukushima, weren’t they, but some have started up again?

That’s right, we’ve seen a couple of them cleared for restart, there’s been a rigorous safety checking process. The Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made it very clear that starting up these reactors is one of his top priorities, not least because Japan is really reliant on nuclear energy for its electricity so it’s had to import all of its energy for the last five years, which has been very, very expensive. So, Shinzo Abe wants to restart these reactors, we’ve seen a couple go back on, and couple of others slated for restart have been quite controversial, a leak was found at one of them. So there’s a lot of fear and resistance in many of the communities around these areas to restarting the reactors in such a seismically active region.

And have the Japanese public generally become quite anti-nuclear because of what happened?

It’s hard to generalise on that. I think there IS a lot of resistance; people think that the costs are too high. They look at the fallout from the Fukushima and think that’s not a risk worth taking. There are still a few hardy protesters outside the foreign ministry in Tokyo here who have been protesting in a make-shift tent for five years – they’re still there. I think people felt quite deceived at the time because they felt that the government and the utility company were not being sufficiently transparent about what was going on so there’s still quite a level of mistrust there.